The University of Manitoba Press has printed a first-of-its-kind book that documents the in-depth experiences of children from Northern Canada, many of whom had to travel great distances and spent months — in some cases, years — away from their families in residential schools.

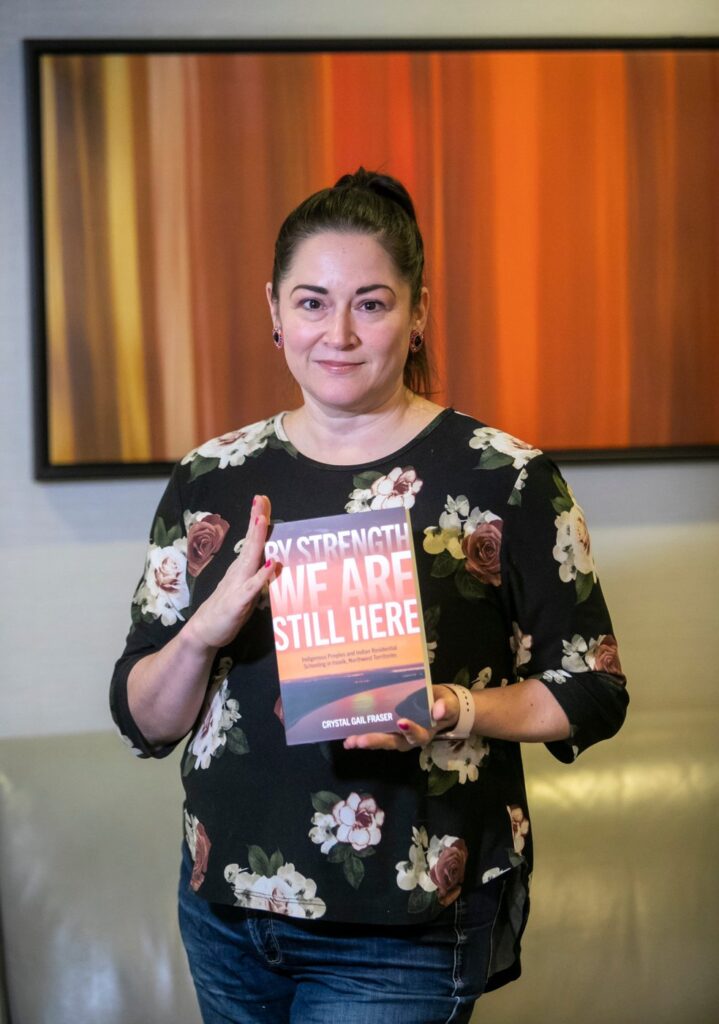

Crystal Fraser, who is Gwichyà Gwich’in and grew up in Inuvik, N.W.T., began her PhD research on the subject in 2010.

“There was this lived experience of seeing things in my community, of wondering about family dynamics, about watching people suffer with addiction and trauma and just never really knowing the story behind that,” she recalled.

“I was curious to get answers about my own life.”

Fraser’s findings are compiled in 384 pages that draw on her experience as an intergenerational survivor, extensive archival work and about 75 interviews she conducted with former students, teachers and administrators over the last 15 years.

By Strength, We Are Still Here: Indigenous Peoples and Indian Residential Schooling in Inuvik, Northwest Territories was officially released Friday.

It is a record of the fallout of government and church-run institutions created to assimilate Indigenous people into mainstream Canadian society in the often-overlooked North and parent pushback to their operations, the author said.

The first chapter opens with a story about a grieving father named Julius Salu, then chief of Teetl’it Gwich’in Band Council in Fort McPherson, N.W.T., in the 1920s.

Salu is said to have declared “No more,” as Anglican missionaries rounded up children aged two and older and loaded them onto boats that travelled more than 2,000 kilometres south to St. Peter’s Residential School in Lesser Slave Lake, Alta., where the chief’s daughter had died.

“Nobody is to send their children away again, not to Hay River, nowhere. If anybody is threatened that they are going to go to court over their children, I’m going to be there. I’m the one who is going to stand there in place of whoever is going to be there. If anybody is going to go to jail for this, I’m taking it,” Salu said.

He then mobilized community members to rebel, gather the children and petition the Department of Indian Affairs to construct a site nearby to keep families intact and ensure youth could access their traditional lands and cultural teachings.

Fraser’s research revealed the request was denied, but she noted the tragic situation has stuck with her and proved formative while putting together her latest publication.

“On the one hand, we have this story of genocide and destruction and colonialism, and we know that about residential schools,” said the associate professor in history and native studies at the University of Alberta in Edmonton.

“But also true, at the same time, is the strength of our people and how they responded.”

Among the activities that sought to dehumanize and assimilate children into Euro-Canadian culture, the book describes how residential schools assigned Inuk and other Indigenous students numbers, made them wear uniforms and forcibly cut their hair.

Inuk artist Angus Cockney was five when he stepped into Grollier Hall in Inuvik, a hostel built for residential school students that would be one of the last such institutions to close its doors, in 1996.

“I was given the number 248, showered, scrubbed, and cleansed. Others were already corralled through. My hair was cut down to the scalp. I was shown my locker. Good thing I was beside my older brother. He was known as 249,” Cockney said in Fraser’s book.

Fraser noted both Grollier and nearby Stringer Hall were architecturally modelled after prisons, and staff members could be on loan from federal prisons.

Northern students’ experiences were unique in that many of them were especially far from home and the institutions built for them operated well into the latter half of the 20th century, she said.

The historian said that area residential schools were well-funded in comparison with southern institutions because they were tied to a national agenda to modernize the North.

That meant there was less of an emphasis on student labour and as a result, children and youth could find community via robust extracurriculars, she said.

Without orders to chop wood for fuel, haul water or take care of farm animals, they had the chance to join student councils, scout groups and ski programs, among other opportunities, Fraser said.

“Student-culture life was given a chance,” she added. “And that’s how a lot of kids made it through.”